A Day in the Life: The Global BGP Table

Update: This article was discussed on Hackernews

Much has been written and a lot of analysis performed on the global BGP table over the years, a significant portion by the inimitable Geoff Huston. However this often focuses on is long term trends, like the growth of the routing table or the adoption of IPv6 , dealing with time frames of of months or years.

I was more interested in what was happening in the short term: what does it look like on the front line for those poor routers connected to the churning, foamy chaos of the interenet, trying their best to adhere to Postel’s Law? What we’ll look at in this article is “a day in the life of the global BGP table”, exploring the intra-day shenanigans with an eye to finding some of the ridiculous things that go on out.

We’ll focus in on three key areas:

- General behaviour over the course of the day

- Outlier path attributes

- Flappy paths

As you’ll see, we end up with more questions than answers, but I think that’s the hallmark of good exploratory work. Let’s dive in.

Let the Yak Shaving Begin

The first step, as always, is to get some data to work with. Parsing the debug outputs from various routers seemed like a recipe for disaster, so instead I did a little yak-shaving. I went back to a half-finished project BGP daemon I’d started writing years ago and got it into a working state. The result is bgpsee, a multi-threaded BGP peering tool for the CLI. Once peered with another router, all the BGP messages - OPENs, KEEPALIVES, and most importantly UPDATEs - are parsed and output as JSON.

For example, heres one of the BGP updates from the dataset we’re working with in this article:

{

"recv_time": 1704483075,

"id": 12349,

"type": "UPDATE",

"nlri": [ "38.43.124.0/23" ],

"withdrawn_routes": [],

"path_attributes": [

{

"type": "ORIGIN", "type_code": 1,

"origin": "IGP"

},

{

"type": "AS_PATH", "type_code": 2,

"n_as_segments": 1,

"path_segments": [

{

"type": "AS_SEQUENCE",

"n_as": 6,

"asns": [ 45270, 4764, 2914, 12956, 27951, 23456 ]

}

]

},

{

"type": "NEXT_HOP", "type_code": 3,

"next_hop": "61.245.147.114"

},

{

"type": "AS4_PATH", "type_code": 17,

"n_as_segments": 1,

"path_segments": [

{

"type": "AS_SEQUENCE",

"n_as": 6,

"asns": [ 45270,4764, 2914, 12956, 27951, 273013 ]

}

]

}

]

}

Collected between 6/1/2024 and 7/1/2024, the full dataset consists of 464,673 BGP UPDATE messages received from a peer (many thanks to Andrew Vinton) with a full BGP table. Let’s take a look at how this full table behaves over the course of the day.

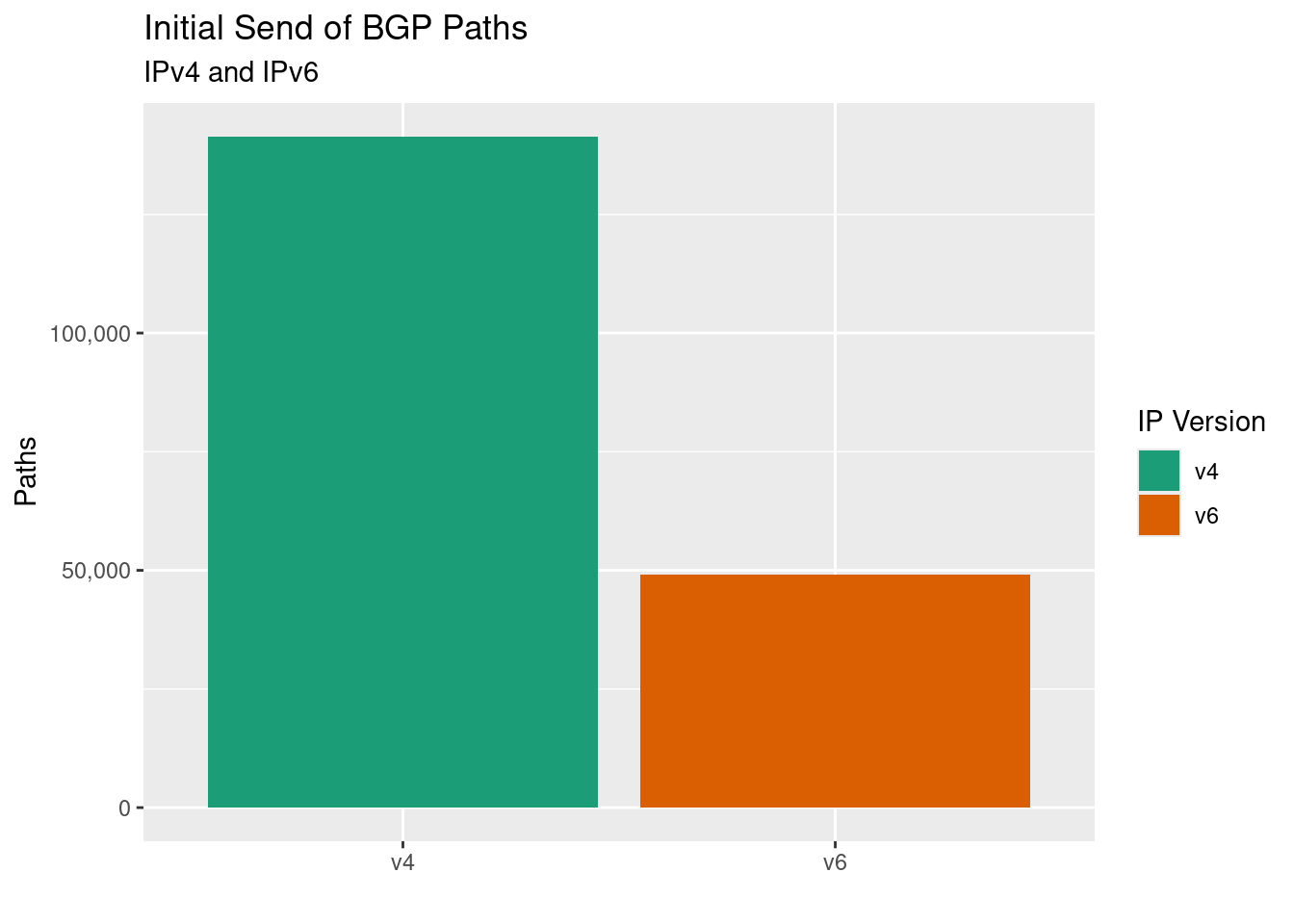

Initial Send, Number of v4 and v6 Paths

When you first bring up a BGP peering with a router you get a big dump of of UPDATEs, what I’ll call the ‘first tranche’. It consists of all paths and associated network layer reachability information (NLRI, or more simply ‘routes’) in the router’s BGP table. After this first tranche the peering only receives UPDATEs for paths that have changed, or withdrawn routes which no longer have any paths. There’s no structural difference between the first tranche and the subsequent UPDATEs, except for the fact you received the first batch in the first 5 or so seconds of the peering coming up.

Here’s a breakdown of the number of distinct paths received in that first tranche, separated by IP version:

It’s important to highlight that this is a count of BGP paths, not routes. Each path is a unique combination of path attributes with associated NLRI information attached, sent in a distinct BGP UPDATE message. There could be one, or one-thousand routes associated with each path. In this first tranche the total number of routes across all of these paths is 949483.

It’s important to highlight that this is a count of BGP paths, not routes. Each path is a unique combination of path attributes with associated NLRI information attached, sent in a distinct BGP UPDATE message. There could be one, or one-thousand routes associated with each path. In this first tranche the total number of routes across all of these paths is 949483.

A Garden Hose or a Fire Hose?

That’s all we’ll look at in the first tranche, we’ll focus our attention from this point on to the rest of the updates received across the day. The updates aren’t sent as a real-time stream, but in bunches based on the Route Advertisement Interval timer, which for this peering was 30 seconds. Here’s a time-series view of the number of updates received during the course of the day:

For IPv4 paths you’re looking on average at around 50 path updates every 30 seconds. For IPv6 it’s slightly lower, at around 47 path updates. While the averages are close, the variance is quite different, a standard deviation of 64.3 and 43 for v4 and v6 respectively.

For IPv4 paths you’re looking on average at around 50 path updates every 30 seconds. For IPv6 it’s slightly lower, at around 47 path updates. While the averages are close, the variance is quite different, a standard deviation of 64.3 and 43 for v4 and v6 respectively.

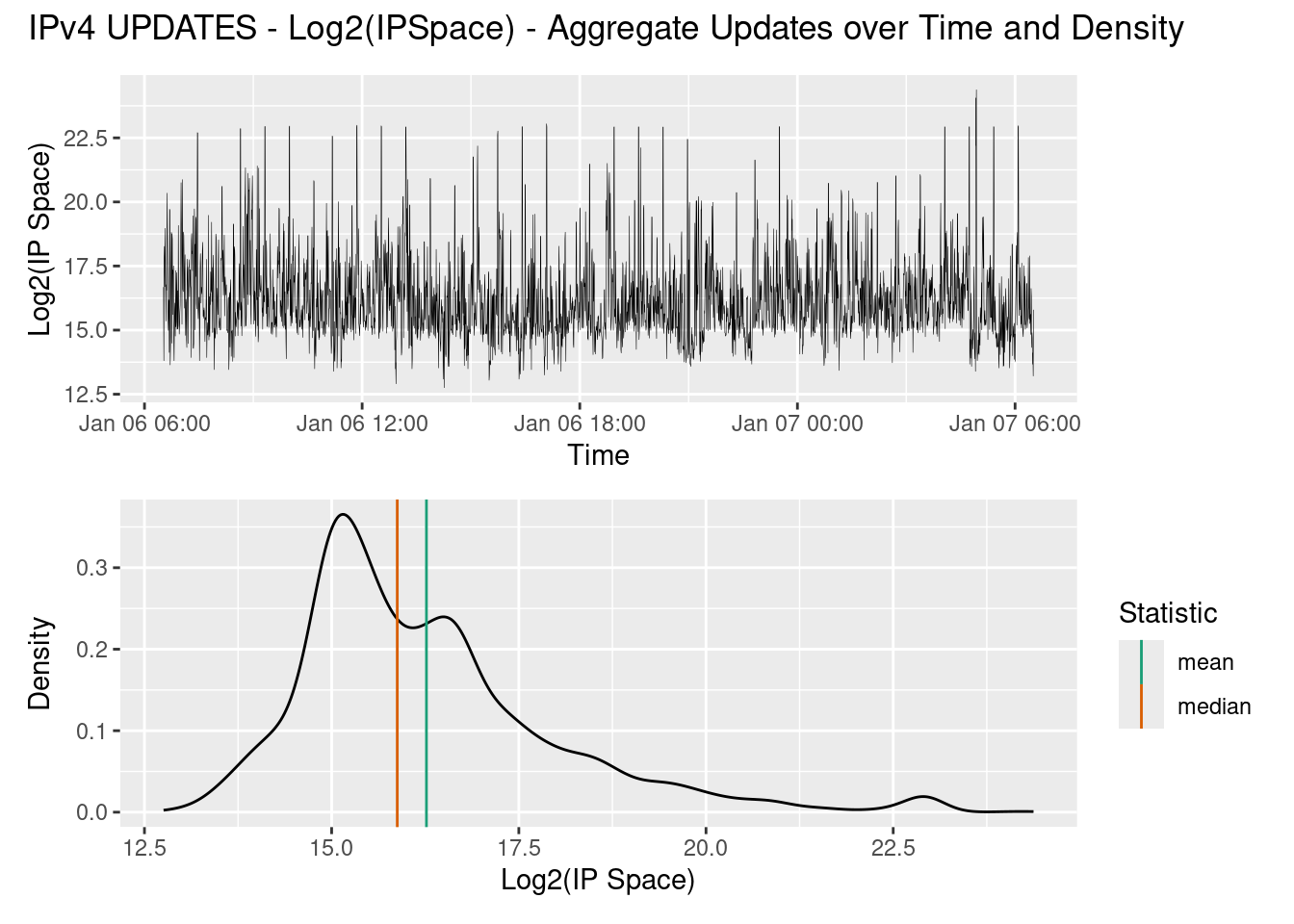

Instead of looking at the total count of updates, we can instead look at the total aggregate IP address change. We do this by adding up the total amount of IP addresses across all updates for every 30 second interval, then take the log2() of the sum. So for example: a /22, a /23 and a /24 would be

Below is the log2() IPv4 address space, viewed as a time series and as a density plot. It shows that on average, every 30 seconds, around 2^16 IP addresses (i.e a /16) change paths in the global routing table, with 95% of time time the change in IP address space is between

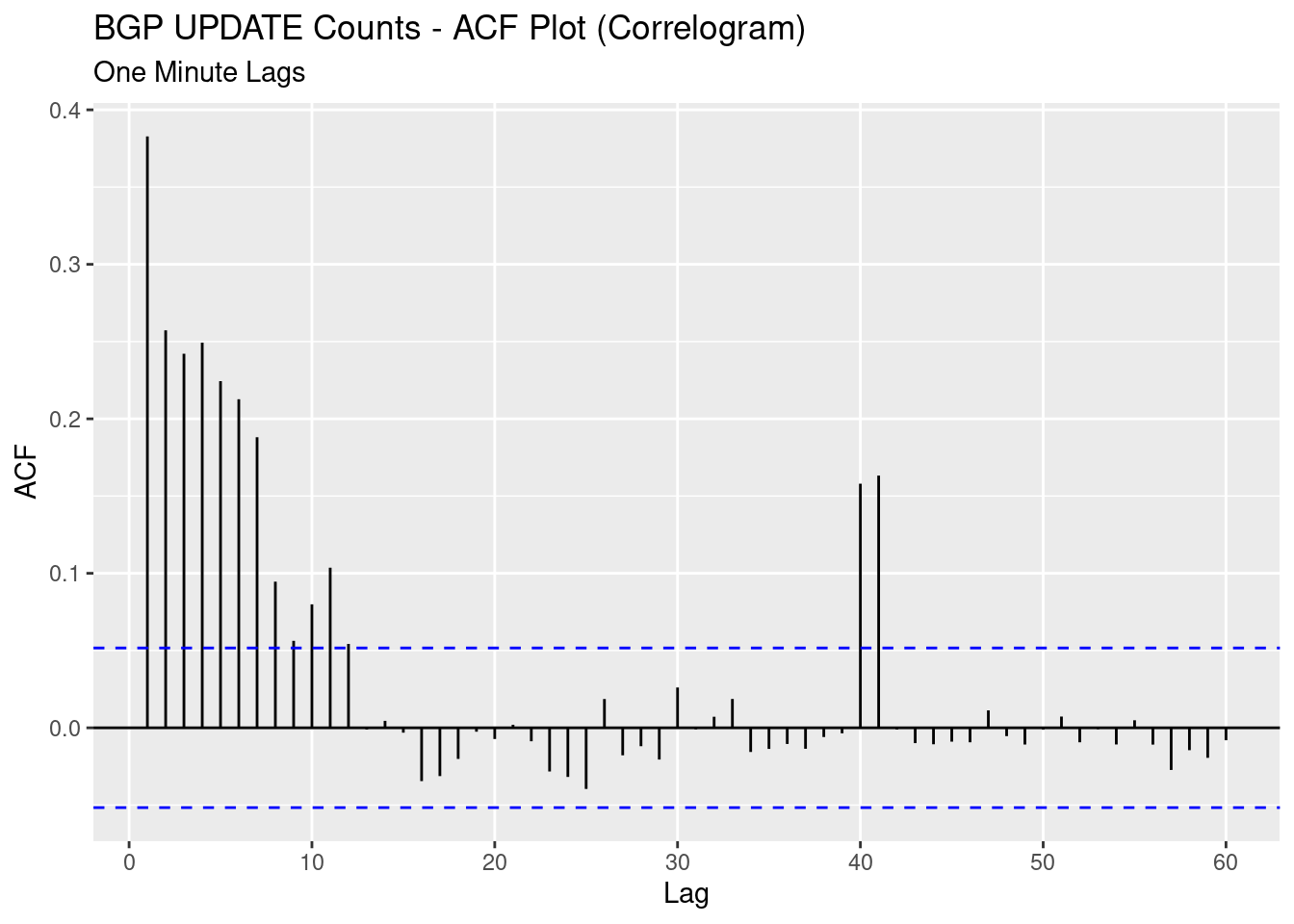

What is apparent in both the path and IP space changes over time is that there is some sort of cyclic behaviour in the IPv4 updates. To determine the period of this cycle we can use an ACF or autocorrelation plot. We calculate the correlation between the number of paths received at time

There is a strong correlation in the first 7 or so lags, which intuitively makes sense to me as path changes can create other path changes as they propagate around the world. But there also appears to be strong correlation at lags 40 and 41, indicating some cyclic behaviour every forty minutes. This gives us the first question which I’ll leave unanswered:

There is a strong correlation in the first 7 or so lags, which intuitively makes sense to me as path changes can create other path changes as they propagate around the world. But there also appears to be strong correlation at lags 40 and 41, indicating some cyclic behaviour every forty minutes. This gives us the first question which I’ll leave unanswered:

- What is causing the global IPv4 BGP table have a 40 minute cycle?.

Prepending Madness

If you’re a network admin, there’s a couple of different ways you can influence how traffic enters your ASN. You can use longer network prefixes, but this doesn’t scale well and you’re not being a polite BGP citizen. You can use the MED attribute, but it’s non-transitive so it doesn’t work if you’re peered to multiple AS. The usual go-to is to modify the AS path length by prepending your own AS one or more times to certain peers, making that path less preferable.

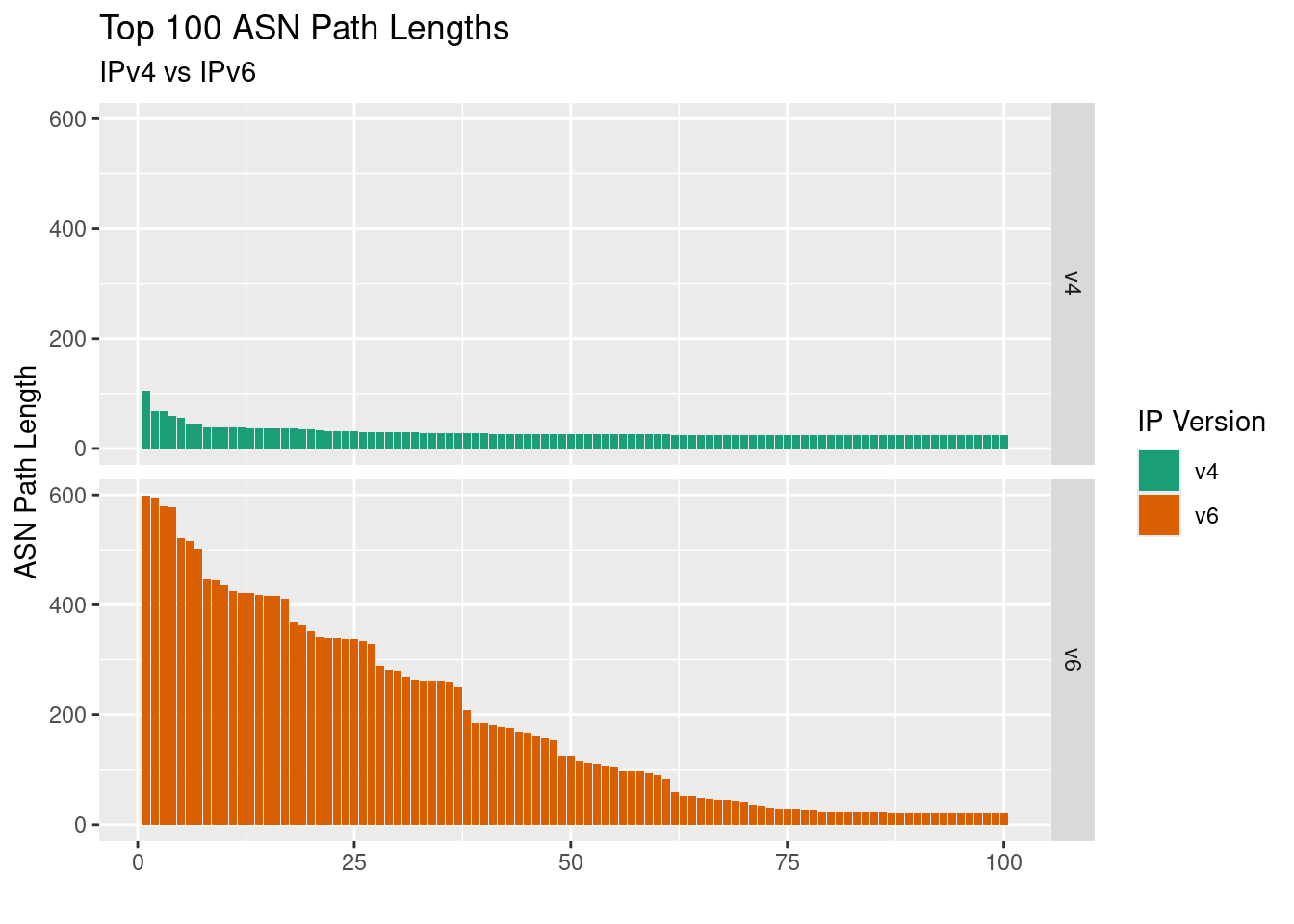

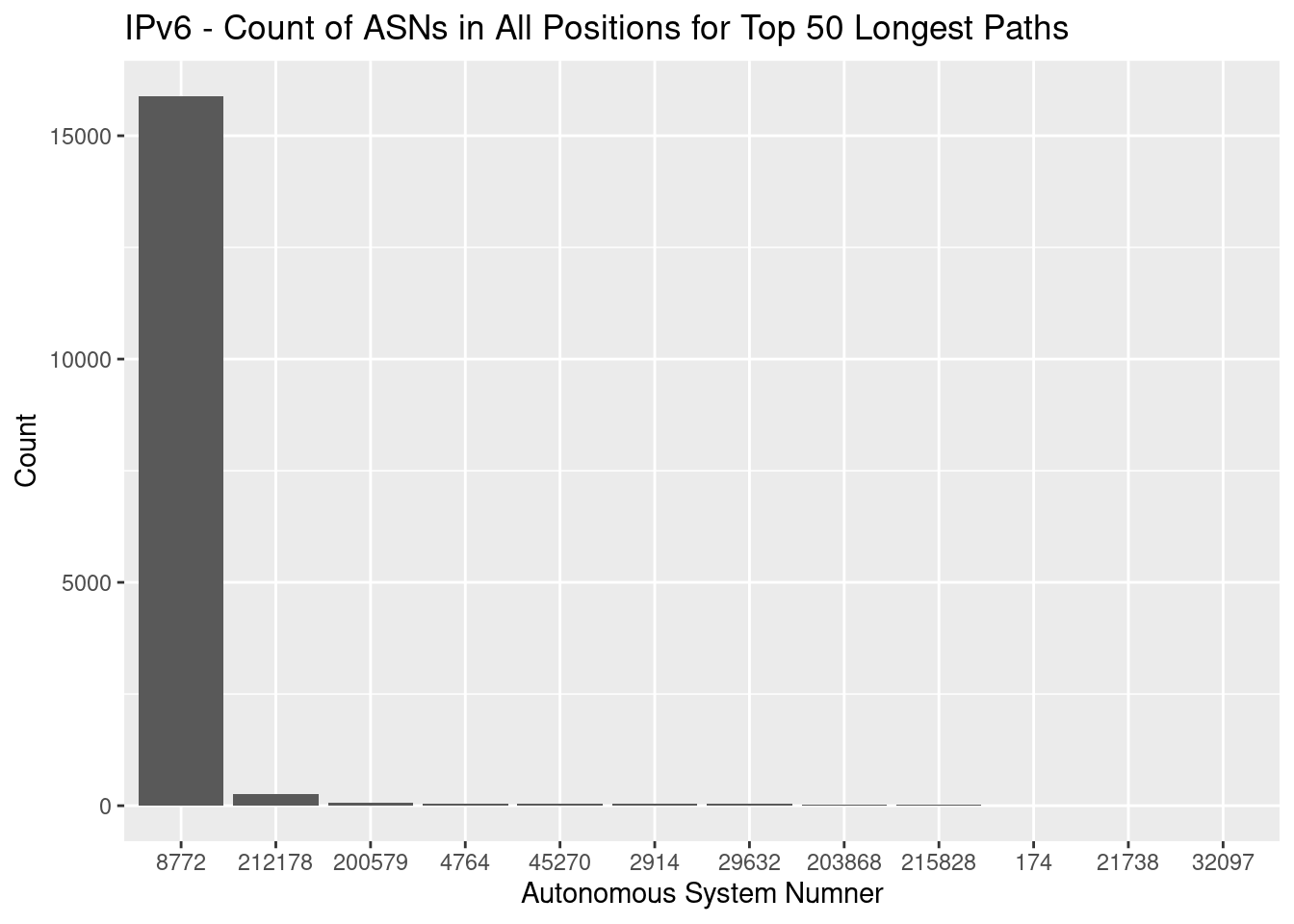

In chaos of the global routing table, some people take this prepending too far. This has in the past caused large, global problems. Let’s take a look at the top 50 AS path lengths for IPv4 and IPv6 updates respectively:

What stands out is the difference between IPv4 and IPv6. The largest IPv4 path length is 105, which is still pretty ridiculous given the fact that the largest non-prepended path in this dataset has a length of 14. But compared to the IPv6 paths it’s outright sensible: top of the table for IPv6 comes in at a whopping 599 ASes! An AS path is actually made up of one or more AS sets or AS sequences, each of which have a maximum length of 255. So it’s taken three AS sequences to announce those routes.

What stands out is the difference between IPv4 and IPv6. The largest IPv4 path length is 105, which is still pretty ridiculous given the fact that the largest non-prepended path in this dataset has a length of 14. But compared to the IPv6 paths it’s outright sensible: top of the table for IPv6 comes in at a whopping 599 ASes! An AS path is actually made up of one or more AS sets or AS sequences, each of which have a maximum length of 255. So it’s taken three AS sequences to announce those routes.

Here’s the longest IPv4 path in all it’s glory with its 105 ASNs. It originated from AS149381 “Dinas Komunikasi dan Informatika Kabupaten Tulungagung” in Indonesia.

[1] "45270 4764 9002 136106 45305 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381 149381"

We see that around 6 hours and 50 minutes later they realise the error in their ways and announce a path with only four ASes, rather than 105:

| recv_time | time_difference | id | as_path_length | type | nlri |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-01-06 06:31:18 | NA | 66121 | 105 | UPDATE | 103.179.250.0/24 |

| 2024-01-06 13:21:35 | 6.84 | 280028 | 4 | UPDATE | 103.179.250.0/24 |

Here’s the largest IPv6 path, with its mammoth 599 prefixes; I’ll let you enjoy scrolling to the right on this one:

[1] "45270 4764 2914 29632 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 8772 200579 200579 203868"

Interestingly it’s not the originator that’s prepending, but as8772 ‘NetAssist LLC’, an ISP out of Ukraine prepending to make paths to asn203868 (Rifqi Arief Pamungkas, again out of Indonesia) less preferable.

Why is there such a difference between the largest IPv4 and IPv6 path lengths? I had a couple of different theories, but then looked at the total number of ASNs in all positions for those top 50 longest paths, and it became apparent what was happening:

Looks like they let the junior network admin at NetAssist on to the tools too early!

Looks like they let the junior network admin at NetAssist on to the tools too early!

Path Attributes

Each BGP update consist of network layer reachability information (routes) and path attributes. For example AS_PATH, NEXT_HOP, etc. There are four kinds of attributes:

- Well-known mandatory

- Well-known discretionary

- Optional transitive

- Optional non-transitive

Section 5 of RFC4271 has a good description of all of these.

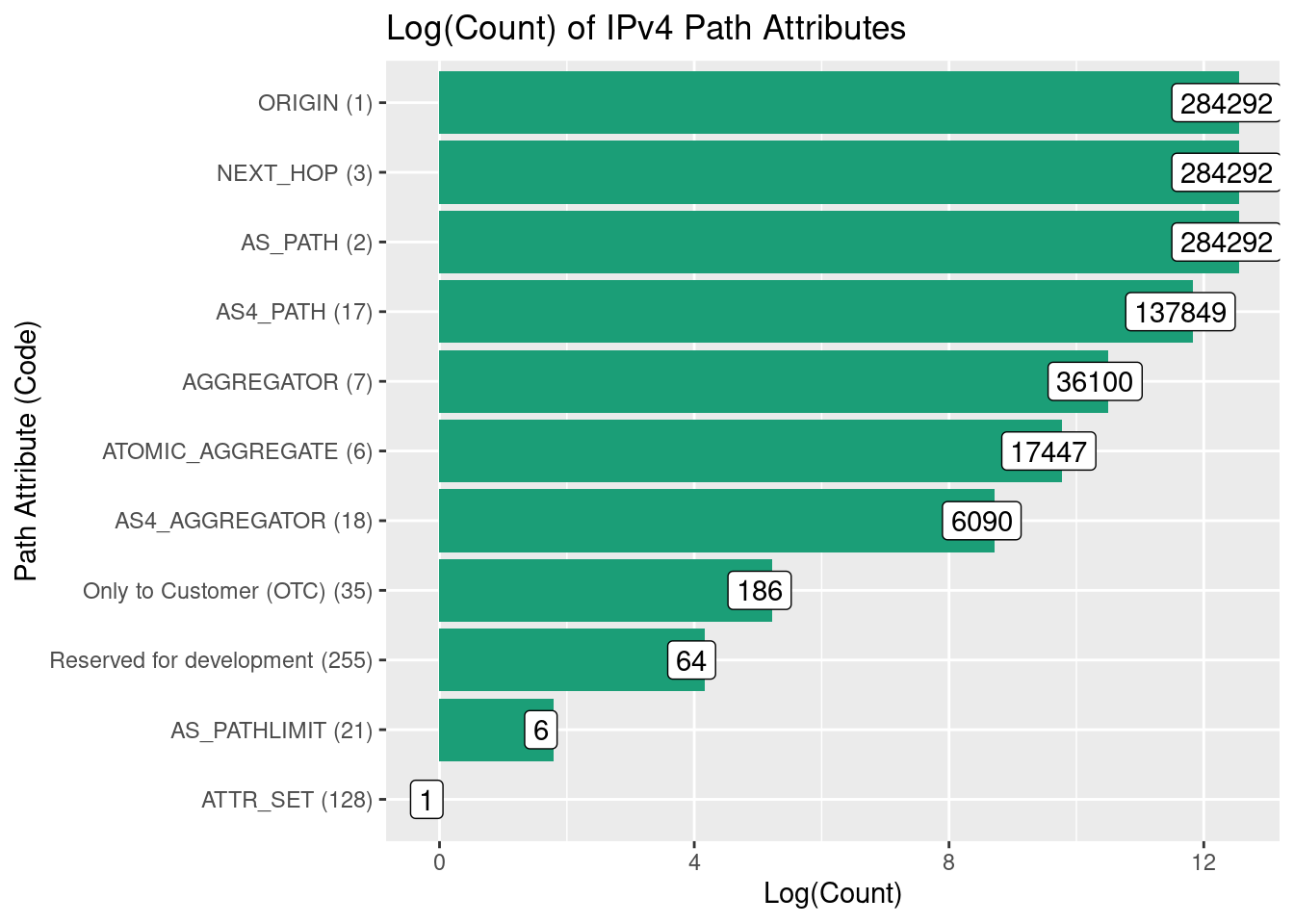

What we can do is take a look at the number of attributes we’ve seen across all of our IPv4 paths, placing this on on a log scale to make it easier to view:

The well-known mandatory attributes, ORIGIN, NEXT_HOP, and AS_PATH, are present in all updates, and have the same counts. There’s a few other common attributes (e.g. AGGREGATOR), and some less common ones (AS_PATHLIMIT and ATTR_SET). However some ASes have attached attribute 255 - the reserved for development attribute - to their updates.

At the time of receiving the updates my bgpsee daemon didn’t save value of these esoteric path attributes. But using routeviews.org we can see that some ASes are still announcing paths with this attribute, and we can observe the raw bytes of its value:

- AS265999 attrib. 255 value: 0000 07DB 0000 0001 0001 000A FF08 0000 0000 0C49 75B3

- AS10429 attrib. 255 value: 0000 07DB 0000 0001 0001 000A FF08 0000 0003 43DC 75C3

- AS52564 attrib. 255 valuue: 0000 07DB 0000 0001 0001 0012 FF10 0000 0000 0C49 75B3 0000 0000 4003 F1C9

Three different ISPs, all announcing paths with this strange path attribute, and raw bytes of the attribute having a similar structure.

This leads us to the second question which I’ll leave here unanswered:

- what vendor is deciding it’s a good idea to use this reserved for development attribute, and what are they using it for?.

Flippy-Flappy: Who’s Having a Bad Time?

Finally, let’s see who’s having a bad time: what are the top routes that are shifting paths or being withdrawn completely during the day. Here’s the top 10 active NLRIs with the number of times the route was included in an UPDATE:

| nlri | update_count |

|---|---|

| 140.99.244.0/23 | 2596 |

| 107.154.97.0/24 | 2583 |

| 45.172.92.0/22 | 2494 |

| 151.236.111.0/24 | 2312 |

| 205.164.85.0/24 | 2189 |

| 41.209.0.0/18 | 2069 |

| 143.255.204.0/22 | 2048 |

| 176.124.58.0/24 | 1584 |

| 187.1.11.0/24 | 1582 |

| 187.1.13.0/24 | 1580 |

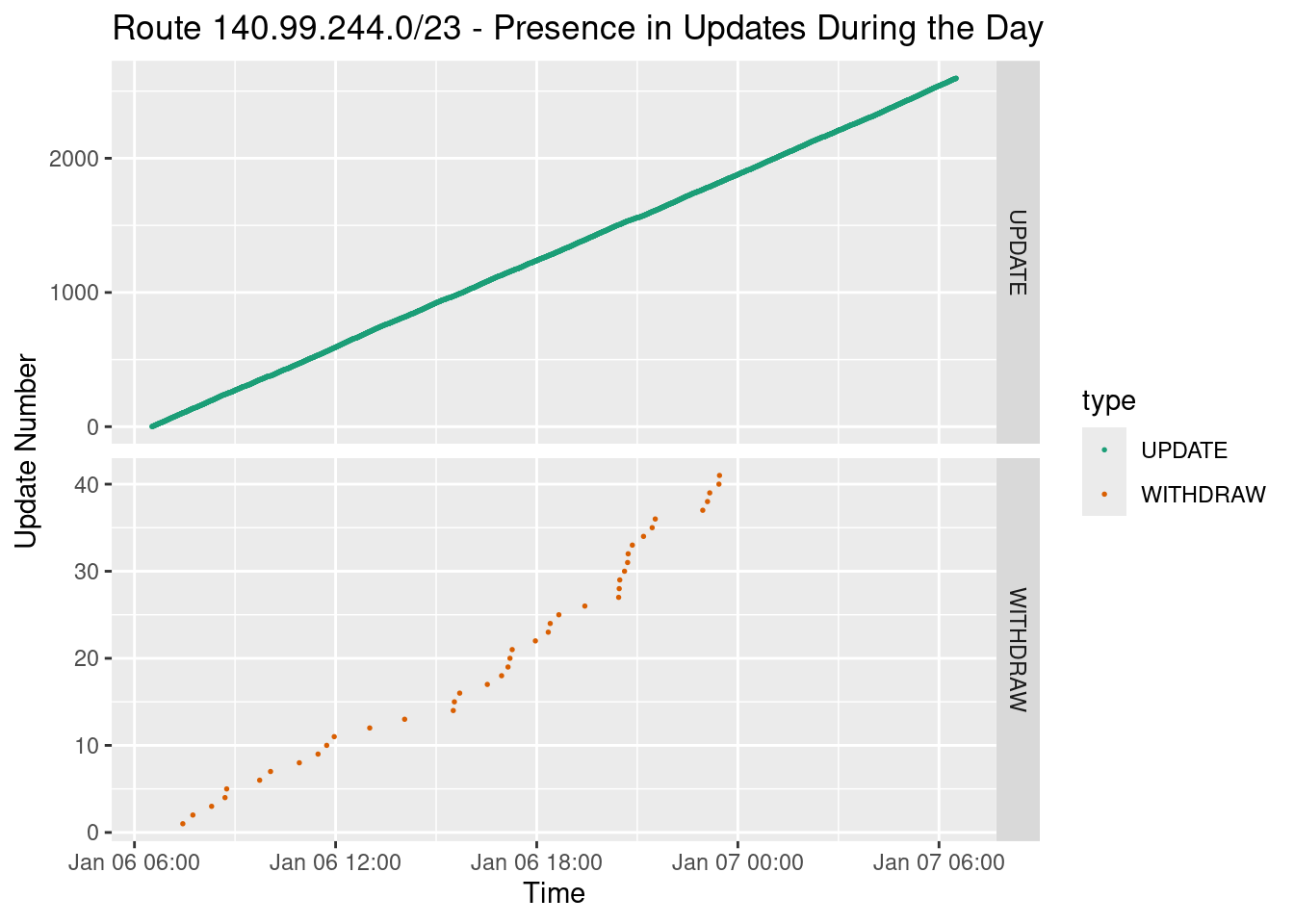

Looks like anyone on 140.99.244.0/23 was having a bad time during this day. This space is owned by a company called EpicUp… more like EpicDown! *groan*.

Graphing the updates and complete withdraws over the course of the day paints a bad picture

The top graph looks like a straight line, but that’s because this route is present in almost every single 30 second block of updates. There are 2,879 30-second blocks and it’s present as either a different path or a withdrawn route in 2,637 of them, or 92.8%!

The top graph looks like a straight line, but that’s because this route is present in almost every single 30 second block of updates. There are 2,879 30-second blocks and it’s present as either a different path or a withdrawn route in 2,637 of them, or 92.8%!

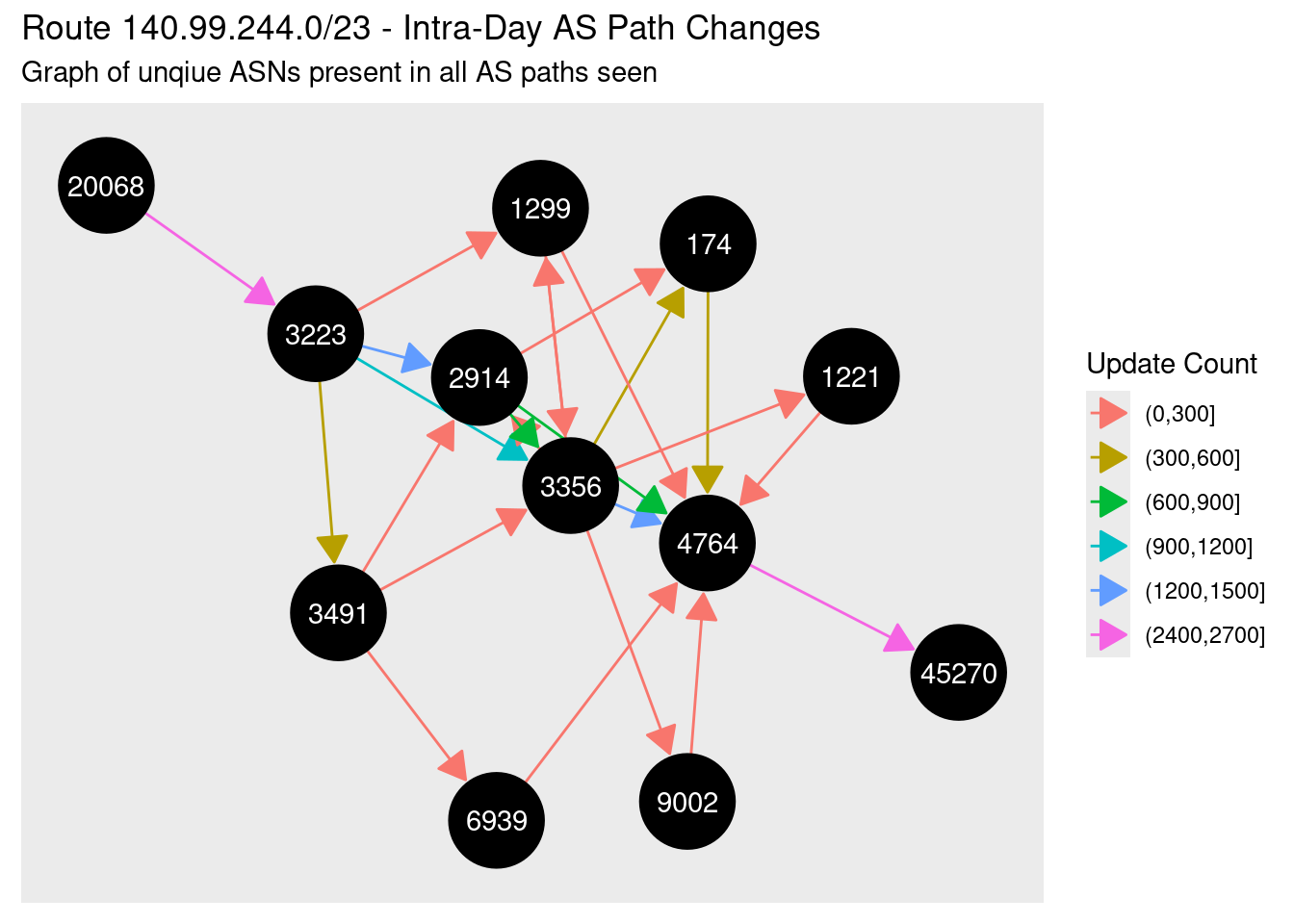

We know the routes is flapping, but how is it flapping, and who is to blame? The best way to visualise this is a graph, with the ASNs in all paths to that network as nodes and edges showing the pairs of ASNs in the paths. I’ve colourised the edges by how many updates were seen with each pair of ASes, binned into groups of 300:

What a mess! You can make out the primary path down the centre through NTT (2914) and Lumen/Level3 (3356), but for whatever reason (bad link? power outages? router crashing?) the path is moving between these tier 1 ISPS and others, including Arelion (1299) and PCCW (3419). While it’s almost impossible to identify the exact reason for the route flapping using this data only, what it does show is the amazing peering diversity of modern global networks, and the the resiliency of a 33 year old routing protocol.

What a mess! You can make out the primary path down the centre through NTT (2914) and Lumen/Level3 (3356), but for whatever reason (bad link? power outages? router crashing?) the path is moving between these tier 1 ISPS and others, including Arelion (1299) and PCCW (3419). While it’s almost impossible to identify the exact reason for the route flapping using this data only, what it does show is the amazing peering diversity of modern global networks, and the the resiliency of a 33 year old routing protocol.

Just The Beginning

There’s a big problem with a data set like this: there’s just too much to look at. I needed to keep a lid on it so this article didn’t balloon out to 30,000 words, but there’s another five rabbit holes I could have gone down. That’s not including the the questions I’ve left unanswered.

With the global BGP table, you’ve got a summary of an entire world encapsulated in a few packets. Your BGP updates could could be political unrest, natural phenomena like earthquakes or fires, or simply a network admin’s fat finger. You’ve got the economics of internet peering, and you’ve got the human element of different administrators with different capabilities coming together to bring up connectivity. And somehow it manages to work, well, most of the time. There’s something both bizarre and beautiful about seeing all of that humanity encapsulated and streamed as small little updates into your laptop.