Git Under the Hood

While I’m not a programmer per se, I do use git almost daily and find it a great tool for source control and versioning of plain text files. But I don’t think there can be any doubt that it is not the easiest tool to use. But despite its unintuitive user interface, under the hood git is quite simple and elegant. I believe that if you can understand the fundamental constructs git uses to store, track, and manage files, then the using git becomes a lot easier.

In this article we’re going to take a look under the covers and investigate git’s fundamental constructs. We’ll start off with its storage model and look at blobs, trees and commits. We’ll see how branches are implemented, and finally we’ll unpack the git index file to understand what happens during the staging of a commit.

There’s already loads of articles out there on git internals, so what’s different about this one? Two things:

- We’re going to avoid the lower level ‘plumbing’ git commands and limit ourselves to the five most common ‘porcelain’ commands:

git {init, add, commit, branch, checkout}. All other work will be done using standard command line utilities. - Using the R packages git2r and tidygraph, we’ll dynamically build up a picture of the connections between git’s objects to help understand how they are tied together.

As always, the source code for this article is available up on github.

Initialisation

We’ll start by initialising a git repository, which creates a .git directory and some initial files. Git holds all of the files and metadata it needs for source control in this directory. To clarify things we’ll prune back as many of the initial files as possible, while still ensuring git recognises it as a valid repository.

# Initialise the repository (quietly)

git init --quiet

# Remove some of the created files and directories

rm -rf .git/{hooks,info,config,branches,description}

rm -rf .git/objects/{info,pack}

rm -rf .git/refs/{heads,tags}

tree .git

.git

├── HEAD

├── objects

└── refs

2 directories, 1 file

With a nice clean slate we can move on to our first object: the blob.

Blobs

The first fundamental git object we’ll look at is the blob. If we create a file and add it to the staging area, we see what has changed in the .git directory.

# Create a file

echo "Root" > file_x

# Add it to the staging area

git add file_x

tree .git

.git

├── HEAD

├── index

├── objects

│ └── 93

│ └── 39e13010d12194986b13e3a777ae5ec4f7c8a6

└── refs

3 directories, 3 files

There’s two new files - an index and an object. We’ll get to the index later in the article, but for now let’s focus on the object. Checking it’s format we find that it’s compressed data:

file .git/objects/93/39e13010d12194986b13e3a777ae5ec4f7c8a6

.git/objects/93/39e13010d12194986b13e3a777ae5ec4f7c8a6: zlib compressed data

Decompressing and looking inside, we see the file is in a structured as a “type, length, value” or TLV. The type is ‘blob’, the length is the size of the of the data (excluding the type), and the value the contents of the file we created:

pigz -cd .git/objects/93/39e13010d12194986b13e3a777ae5ec4f7c8a6 | hexdump -C

00000000 62 6c 6f 62 20 35 00 52 6f 6f 74 0a |blob 5.Root.|

0000000c

How is the path to the blob object created? It’s simply the SHA1 hash of the blob itself. The first two hexadecimal digits are used as a folder, with the remaining digits used as the object file name. We can show this by recreating the object, taking the hash, and noting it’s the same as our object’s path:

# The hash matches the object's path

echo "blob 5\0Root" | shasum

9339e13010d12194986b13e3a777ae5ec4f7c8a6 -

It can therefore be helpful to understand git as a form of content addressable storage: the location of the data that is under its control is based on the content of the data itself. Let’s explore this further: we’ll add two files with the same contents, one in the root directory and one in a subdirectory.

# Cerate a subdir

mkdir subdir

# Add two files, one in the root, one in the subdir

echo "Root & Sub" > file_y

echo "Root & Sub" > subdir/file_z

# Add the files to the staging area

git add file_y subdir

tree .git

.git

├── HEAD

├── index

├── objects

│ ├── 93

│ │ └── 39e13010d12194986b13e3a777ae5ec4f7c8a6

│ └── cc

│ └── 23f67bb60997d9628f4fd1e9e84f92fd49780e

└── refs

4 directories, 4 files

While we’ve added three files but there’s only two objects. Blobs only contain raw data, with no reference to files or directories. There’s only two pieces of unique data, and thus two objects. The file/directory information is stored in tree objects which we will take a look at in the next section.

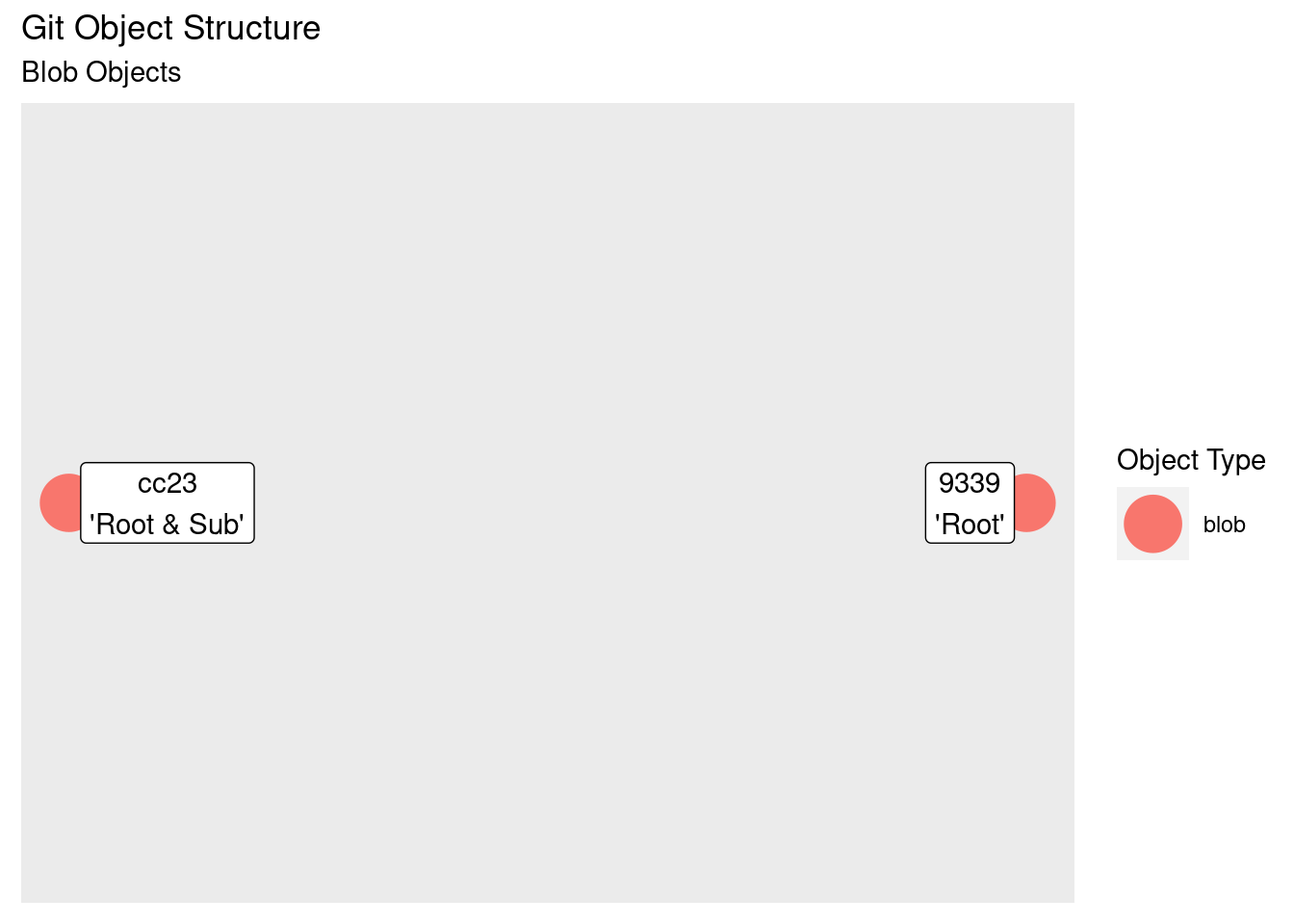

Over the course of the article we’re going to build up a graph of the objects in the git repository to gain a visual representation of the structure. Here’s our starting point: two blobs, the first four characters of their hash, and their contents:

The two little blobs of data look pretty lonely out there. What they need is some context, and this is where the tree object comes in.

Tree

As we’ve seen, there’s no file or directory information in the blob object. The storage of this information is the role of the tree object. Let’s perform our first commit and see what’s changed in the repository:

git commit --quiet -m "First Commit"

tree .git

.git

├── COMMIT_EDITMSG

├── HEAD

├── index

├── logs

│ ├── HEAD

│ └── refs

│ └── heads

│ └── master

├── objects

│ ├── 36

│ │ └── 58bfd8a7cda8ee50181497ab8ec4e699428877

│ ├── 4e

│ │ └── eafbc980bb5cc210392fa9712eeca32ded0f7d

│ ├── 67

│ │ └── 21ae08f27ae139ec833f8ab14e3361c38d07bd

│ ├── 93

│ │ └── 39e13010d12194986b13e3a777ae5ec4f7c8a6

│ └── cc

│ └── 23f67bb60997d9628f4fd1e9e84f92fd49780e

└── refs

└── heads

└── master

11 directories, 11 files

A lot has changed and at first glance it may be a bit overwhelming, but focus in on the objects subdirectory. There’s an additional three objects on top of the two blob objects we saw before. What are they? If you’ll forgive me, I’ll use a very ugly set of commands to pull out the type and length from each of the objects:

# May god have mercy on my soul

find .git/objects -type f -exec sh -c \

"echo -n '{} -> ' && pigz -cd {} | perl -0777 -nE 'say unpack qw(Z*)'" \;

.git/objects/cc/23f67bb60997d9628f4fd1e9e84f92fd49780e -> blob 11

.git/objects/36/58bfd8a7cda8ee50181497ab8ec4e699428877 -> commit 175

.git/objects/4e/eafbc980bb5cc210392fa9712eeca32ded0f7d -> tree 101

.git/objects/67/21ae08f27ae139ec833f8ab14e3361c38d07bd -> tree 34

.git/objects/93/39e13010d12194986b13e3a777ae5ec4f7c8a6 -> blob 5

So in addition to our two blobs, we’ve got two trees and a commit. Our starting point for will be the first of the tree objects. Unlike the others, trees contain some binary information rather than UTF-8 strings. I’ll use Perl’s unpack() function so decode this into hexadecimal:

pigz -cd .git/objects/4e/eafbc980bb5cc210392fa9712eeca32ded0f7d |\

perl -nE 'print join "\n", unpack("Z*(Z*H40)*")'

tree 101

100644 file_x

9339e13010d12194986b13e3a777ae5ec4f7c8a6

100644 file_y

cc23f67bb60997d9628f4fd1e9e84f92fd49780e

40000 subdir

6721ae08f27ae139ec833f8ab14e3361c38d07bd

Like the blob we have the type and length of the object. Following this there’s an entry for each of the two files and the subdirectory that reside in the root directory. The digits preceding the file name are the mode, capturing the type of filesystem object (regular file/symbolic link/directory) and its permissions. Git doesn’t track all combinations of permissions, only whether the file is user executable or not.

Each of the the two file entries point to the hashes of the blob objects, but the subdirectory points to the hash of another tree object. Looking inside that tree object:

pigz -cd .git/objects/67/21ae08f27ae139ec833f8ab14e3361c38d07bd |\

perl -nE 'print join "\n", unpack("Z*(Z*H40)*")'

tree 34

100644 file_z

cc23f67bb60997d9628f4fd1e9e84f92fd49780e

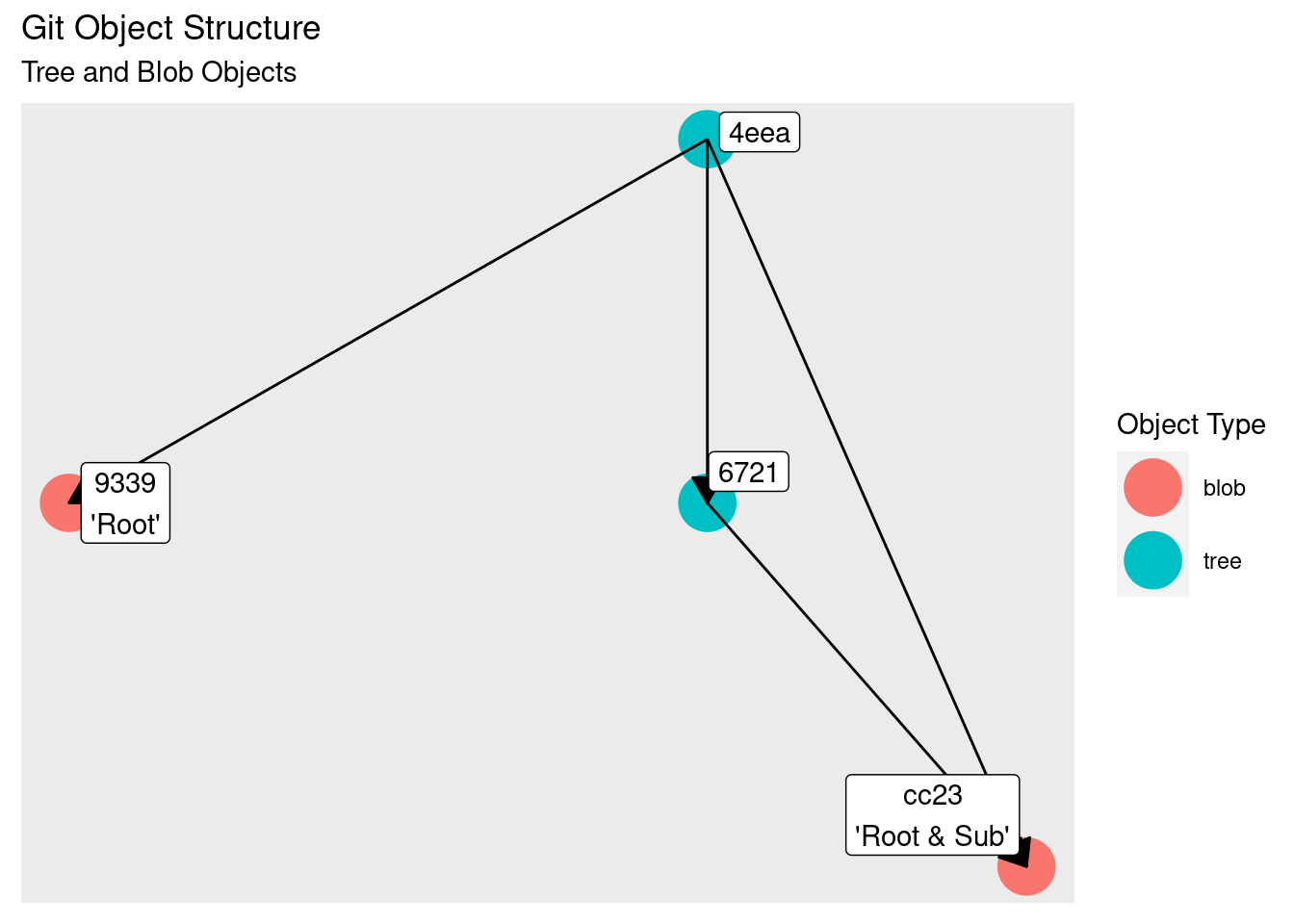

We see this has an entry for the file_z in the subdirectory, and this points to the same hash as the file_y entry in the previous tree. A graph should make this clearer:

At the top is the root of the tree, with vertices to the two blobs (file_x and file_y) and a tree (the subdirectory). The second tree is has a single vertex to a blob (file_z). The root and subdirectory trees both point to the same blob, because both files have the same contents.

At the top is the root of the tree, with vertices to the two blobs (file_x and file_y) and a tree (the subdirectory). The second tree is has a single vertex to a blob (file_z). The root and subdirectory trees both point to the same blob, because both files have the same contents.

With blobs and trees we’ve built up a pseudo-filesystem, but how does this help us with source control? The object that ties all of this together is the commit.

Commit

Our third object - and the one most visible to the end user - is the commit. We’re going to open our commit up, but as we’ll learn about shortly, the hash of the commit (and thus the path to the object) depends partially on the time the commit was made. As I generate this article dynamically, there’s a little bit of overhead to get the commit object:

# Get the commit object

COMMIT_DIR=$(cut -c 1-2 .git/refs/heads/master)

COMMIT_OBJ=$(cut -c 3- .git/refs/heads/master)

# Open it up

pigz -cd .git/objects/$COMMIT_DIR/$COMMIT_OBJ |\

perl -0777 -nE 'print join "\n", unpack("Z*A*")'

commit 175

tree 4eeafbc980bb5cc210392fa9712eeca32ded0f7d

author Greg Foletta <greg@foletta.org> 1654027280 +1000

committer Greg Foletta <greg@foletta.org> 1654027280 +1000

First Commit

Again we have the type and length of the object at the start, then there’s a few different pieces of information.

The first is reference to a tree object. This is the tree object that represents the root directory of the repository. The next is the author of the commit, with their name, email address, commit time and the UTC offset. As the person who authored the commit doesn’t necessarily have to be the person who committed it to the repository, there’s also a line for the committer. Following this is the commit message, which is free text input entered at the time of the commit.

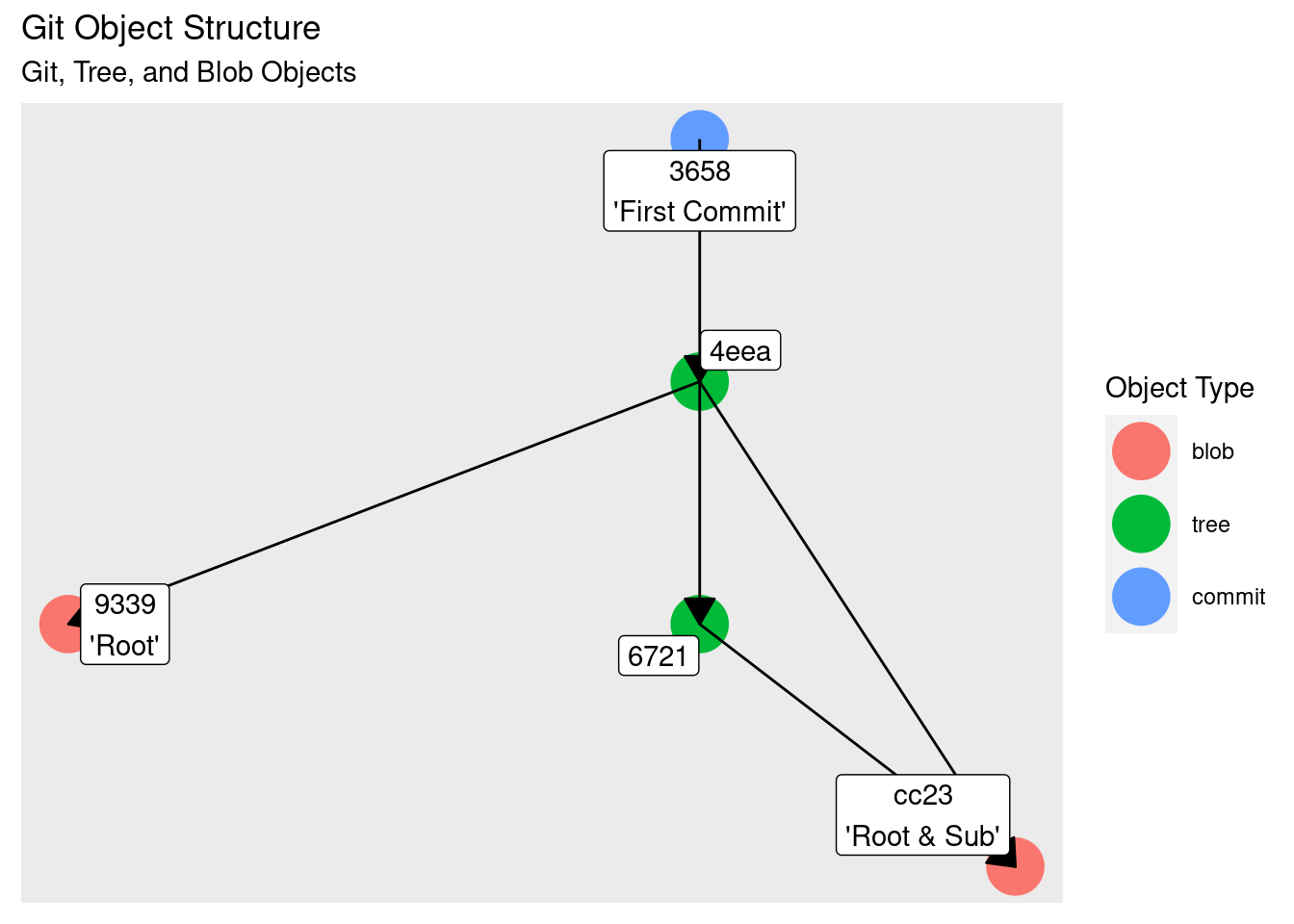

Let’s place this on our graph:

The commit points to the tree object representing the root directory. But this first commit is a special commit, missing a piece of information: parents. Every other commit in this repository from this point onwards will point to one or more parent entries. This creates a directed acyclic graph (DAG), allowing any commit to be traced back to the first commit. As every commit’s hash is dependent on its parents’ hash, the graph is also a form of Merkle tree.

The commit points to the tree object representing the root directory. But this first commit is a special commit, missing a piece of information: parents. Every other commit in this repository from this point onwards will point to one or more parent entries. This creates a directed acyclic graph (DAG), allowing any commit to be traced back to the first commit. As every commit’s hash is dependent on its parents’ hash, the graph is also a form of Merkle tree.

If we change the contents of file_z, stage, and create a second commit, will allow us to see this additional information in the commit object:

# Change the contents, add, and create a second commit

echo "Root Changed" > file_x

git add file_x

git commit -q -m "Second Commit"

# Determine the path to the second commit object

COMMIT_DIR=$(cut -c 1-2 .git/refs/heads/master)

COMMIT_OBJ=$(cut -c 3- .git/refs/heads/master)

# Unpack the contents of the commit

pigz -cd .git/objects/$COMMIT_DIR/$COMMIT_OBJ |

perl -0777 -nE 'print join "\n", unpack("Z*A*")'

commit 224

tree 6e09d0dbb13d342d66580c40a49dd1583958ccc8

parent 3658bfd8a7cda8ee50181497ab8ec4e699428877

author Greg Foletta <greg@foletta.org> 1654027282 +1000

committer Greg Foletta <greg@foletta.org> 1654027282 +1000

Second Commit

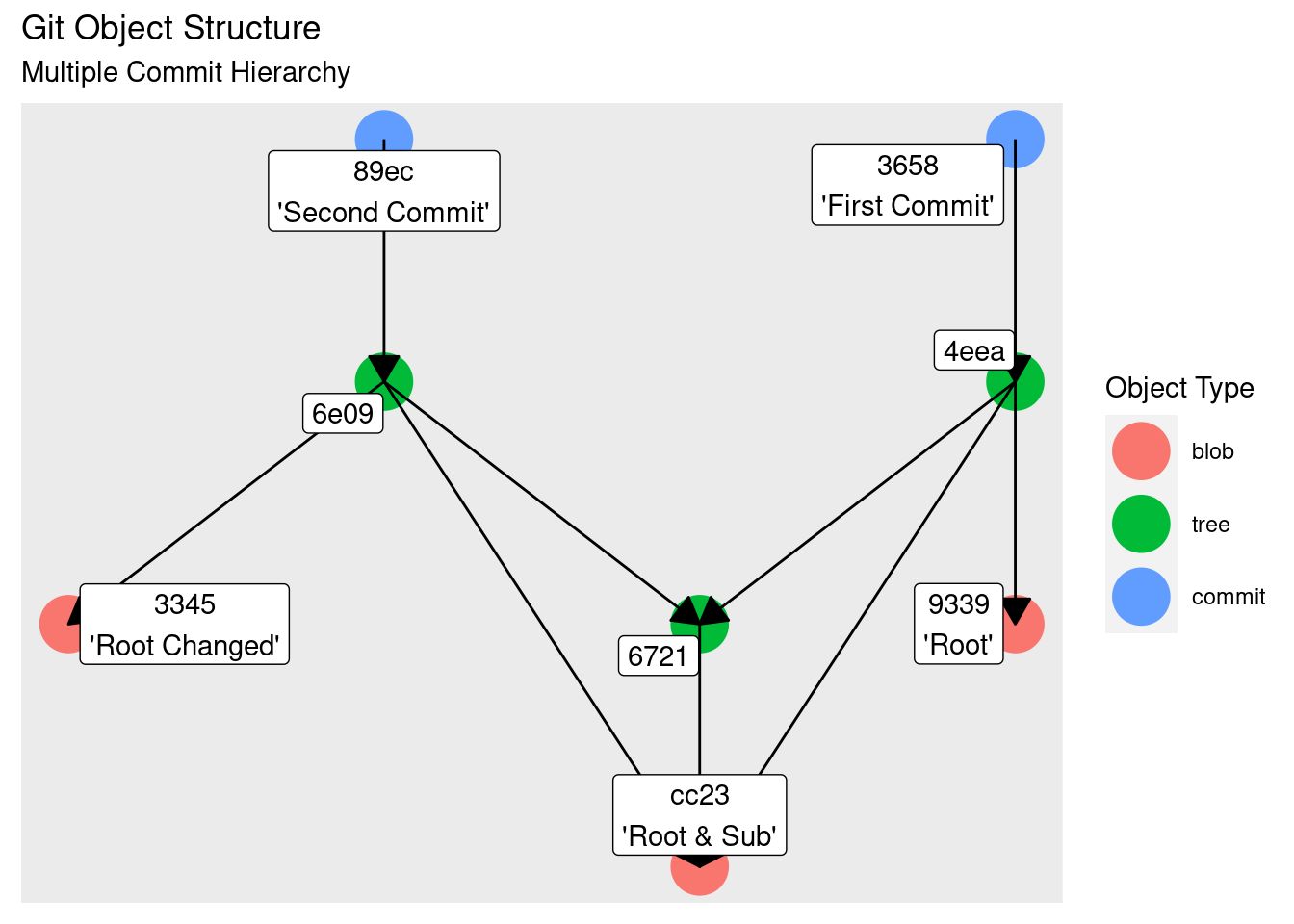

We can then place the second commit onto our graph, omitting the link back to the parent (we’ll get to that in the next section):

What we see here represents the core of how git stores data. The commits represent ‘snapshots’ of the state of the files and directories in the repository. In this particular scenario commits point to different root tree objects, each of which point to different objects representing the file_x. But they share the same tree object representing the subdirectory and the blob representing file_y.

What we see here represents the core of how git stores data. The commits represent ‘snapshots’ of the state of the files and directories in the repository. In this particular scenario commits point to different root tree objects, each of which point to different objects representing the file_x. But they share the same tree object representing the subdirectory and the blob representing file_y.

There’s no ‘diffs’ calculated between commits; if one byte changes in a file, a new blob is created, resulting in a new tree (or trees), resulting in a new commit. In terms of the space-time trade-off, git chooses space over time, resulting in a simple model of data changes over time.

The problem is, our commits are still addressed via a 160 bit hash. This is all well and good for a computer, but we’d like something a bit more human friendly. This is the role of branches.

Branches and HEAD

Branches are relatively simple: they are a human-friendly, named pointer to a commit hash. Local branches (as opposed to remote branches, which we won’t cover in this article) are stored in .git/refs/heads/, and right now the current master1 branch points to the hash of our second commit:

cat .git/refs/heads/master

89ec2b06b21f25cdbd763924c751c8b24886d5c2

We also need to briefly mention HEAD. This file tracks which commit is currently ‘active’, i.e. the checked out files match those in the commit. We see HEAD currently refers to our master branch2:

cat .git/HEAD

ref: refs/heads/master

If we create a new branch, it will recurse on what HEAD points to until it finds a commit:

# Create a new branch

git branch branch_2

# List the branches and the hashes they point to

find .git/refs/heads/* -type f -exec sh -c 'echo -n "{} -> " && cat {}' \;

.git/refs/heads/branch_2 -> 89ec2b06b21f25cdbd763924c751c8b24886d5c2

.git/refs/heads/master -> 89ec2b06b21f25cdbd763924c751c8b24886d5c2

When a new commit is issued, the current branch is moved to point to the new commit (and head will indirectly point to the commit through this branch):

# Checkout a branch and commit on it

git checkout -q branch_2

echo $RANDOM > file_x

git commit -q -am "Third Commit (branch_2)"

# The 'new_branch' branch now points to a different commit.

find .git/refs/heads/* -type f -exec sh -c 'echo -n "{} -> " && cat {}' \;

.git/refs/heads/branch_2 -> 54d46328e009399d656f158c04df8ad9c2b24cf6

.git/refs/heads/master -> 89ec2b06b21f25cdbd763924c751c8b24886d5c2

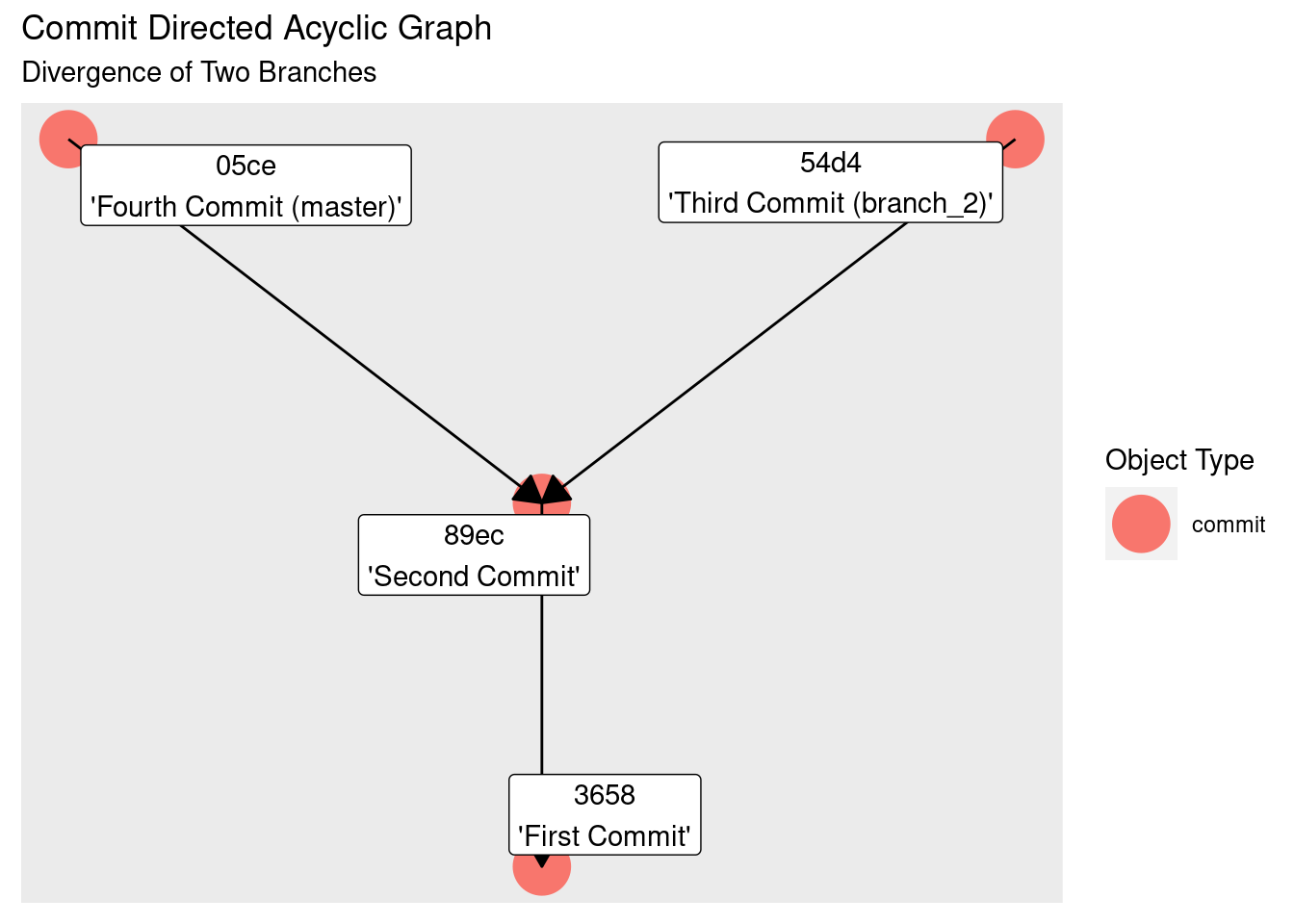

If we checkout the master branch and creating a new commit, we ca visualise how the two branches have diverged:

# Commit back on the master branch

git checkout -q master

echo $RANDOM > file_x

git commit -q -am "Fourth Commit (master)"

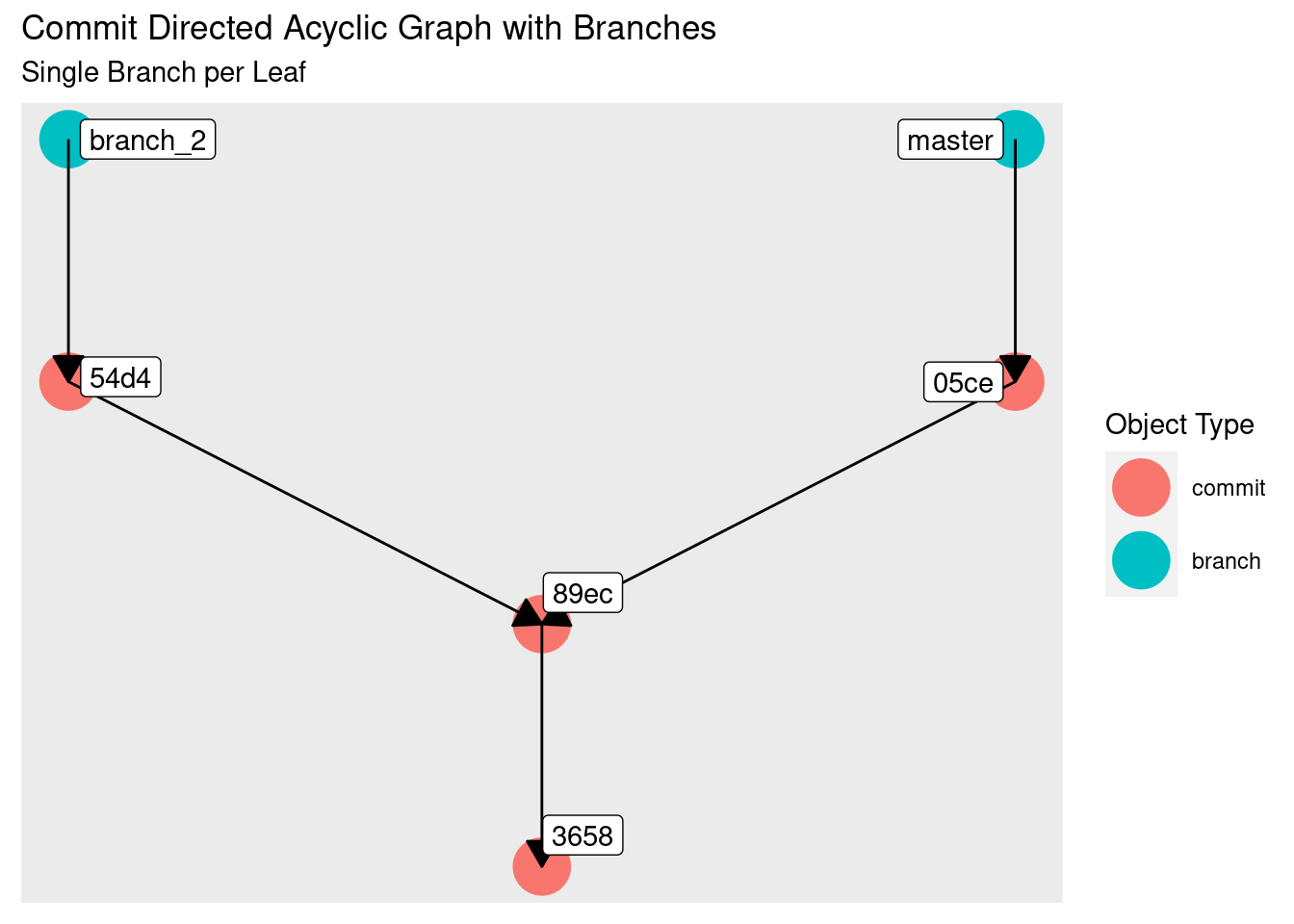

The third and fourth commits are both descendants of the third commit. Adding in our branches to the graph we see they point to the tip of this graph:

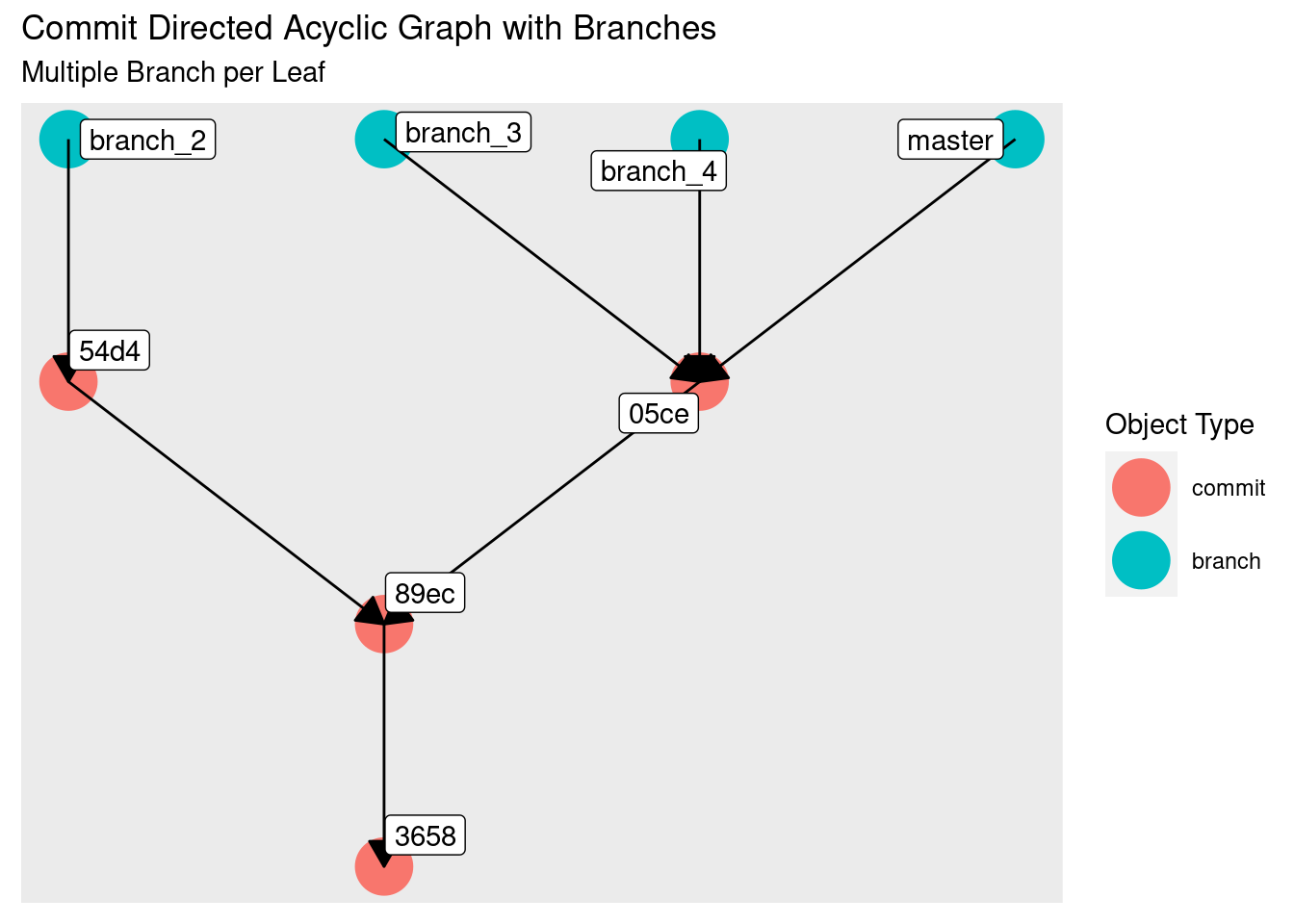

There’s nothing stopping us from creating more branches, even if they point to the same location:

There’s nothing stopping us from creating more branches, even if they point to the same location:

# Create new branches

git branch branch_3

git branch branch_4

The key takeaway is that branches provide a human-friendly way of navigating the git’s commit DAG.

Index

The final file we’re going to look at is the index. While it has a few purposes, we’ll focus on it’s main role as the ‘staging area’. The exact structure is available here, and I’ve converted this into Perl unpack() language:

perl -0777 -nE '

# Extract out each file in the index

my @index = unpack("A4 H8 N (N4 N2 n B16 N N N H40 B16 Z*)");

say "Index Header: " . join " ", @index[0..2];

say "lstat() info: " . join " ", @index[3..12];

say "Object & Filepath: " . join " ", @index[13..16];

' .git/index

Index Header: DIRC 00000002 3

lstat() info: 1654027283 118849971 1654027283 118849971 64769 7734889 0 1000000110100100 1000 1000

Object & Filepath: 6 511c5ae2b662376b23658fe922231d824d4e03e6 0000000000000110 file_x

The first line shows the the four byte ‘DIRC’ signature (which stands for ‘directory cache’), the version number, and the number of entries (files in the index). We’ve only unpacked one of the files.

The first fields contain information from the lstat(2) function: last changed and modified time, the device and inode, permissions, uid and gid, and file size. These values allow git to quickly determine if files in the working tree have been modified.

Then comes the hash of the object, a flags field (which includes the length of path), and the path to the object.

If we recall back in the blobs section, when we added a file to the staging are via git add, the index was created. Let’s modify file_x and add it to the staging area:

echo "Index Modification" > file_x

git add file_x

Now we’ll re-take a look at the index:

ctime, mtime: 1654027286 1654027286

object, filepath: db12d29ef25db0f954787c6d620f1f6e9ce3c778 file_x

The create and modify times have changed, and so has the object that file_x points to. If a git commit is issued, the tree underlying the commit is based upon the current state of this index. When a different branch is checked out, the index is rebuilt so that the files in index point to the correct blobs for that particular commit.

Conclusion

In this article we dived in to the internals of git. We’ve looked at git’s data model and learned about the raw blobs of data, the trees that hold the filesystem information, and the commits that point the root of the tree. We’ve seen how commits have parents, creating a directed acyclic grapg of differing states of the repository.

Branches were shown to be quite simple, human-readable pointers to commit hashes, allowing us to navigate around git’s commit graph. Finally we cracked open index, which is a staging area for the next commit.

It’s perhaps a sad indictment when you have to understand the internals of something in order to use it. This could be bad design, the inherent complexity of the problem domain, or perhaps a little bit of both. Nevertheless git is a widely used tool that’s incredibly powerful, and investing some time to understand it will surely pay dividends down the line when want to manage configuration, code, or almost any other type of text-based content.